This is originally an essay I made for the anthropology class during my exchange program. We had to pick any ethnography and make a critical review of it. I chose The Passing of Aborigines (1938), by Daisy May Bates. The monograph, which is emphasized by its title, provided a form of salvage ethnography with a spirit to reserve a memory bank of Aboriginal ‘remnants’ during transition of Western people settlement in Australia.

Among ubiquitous works which covered the massive interest towards the same subject, Bates provided a distinctive and even extreme research method by devoting almost 35 years of her life to live in the natural habitat of Aboriginal people that she called “my natives”. In her essay “Colonial Women in the Australian Dictionary of Biography”, Barbara Dawson (2007) described Bates character as presenting an enigmatic dichotomy of both sympathy and Imperial attitudes of racial superiority towards Aborigines. Accordingly, to understand the author’s eccentric fieldwork situation and her contradictory views, a mixed of biographical and historical approach to examine the ethnography. How does this ethnography portray heroism and ethnocentrism in the early anthropology? How does the relationship with its context took place in the framework of colonized Australia?

|

| Collage that I made, inspired by a chapter in the book "My Friends, The Birds" |

OVERVIEW OF THE PASSING OF ABOROGINES

The Passing of Aborigines is situated in the broader context of ethnographic prose. Daisy Bates was a self made anthropologist with a background in journalism. Given that in the late 1800s, there was a division of labour between the professional anthropologist and the amateur fieldworker,with the former remaining in the library and museum and the latter travelling to remote parts of the world collecting ethnological materials, Bates deployed the latter and began to cover the theme without formal education of the field.

In 1904, Daisy Bates, an Irish-born woman in her forties who had temporarily worked as governess in Queensland and a ‘lady journalist’ in London, began to collect material for her ‘compilation of a history and vocabulary’ of the Western Australian Aborigines. She was doing so with the support of the Registrar General of Western Australia, Henry Prinsep, who also appointed her Honorary Protector of the Aborigines.

She was known as a strict dresser by consistently wearing black Edwardian costumes with a Victorian neck shirt even in the blazing heat of Australia. Despite of the eccentricity, she managed to immerse herself among the Aboriginal natives and at the end of her life, she was remembered as The White Queen of the Never Never. Arthur Mee, a British author who wrote the preface in her 1938 book, aligned her name with Florence Nightingale and Father Damien due to her sacrificing spirit to nurture the significantly dying race. Her graceful reputation remained until her death in 1951, in which her name was even mentioned in Australian curriculum and her story was adapted into several theatrical play.

There were some earlier reviews conducted by several Australian anthropology scholars such as A.C. Haddon (1939), K.O.L Burridge (1966), and William W. Wood (1968), in which most of them responded positively regarding the book. The Passing of Aborigines, as expressed in its title, was positioned itself in the salvage anthropological, the recording of the practices and folklore of cultures threatened with extinction, with a spirit to record the almost extinct race of Australian Aborigines. Eventually the claim was proved wrong a few decades later when by the year of 1970s the indigenous groups embraced a new politically assertive right. Since then, her work gradually became less respected. Furthermore, the unpopularity of the work was getting worse since a research by a Queensland historian, Alan Queale, had thrown up some fascinating new facts about Bates which were outlined by Isobel White (1985). It seemed that Bates told a number of significant lies about her early life. (Colley 3) Firstly, she lied about her initial name which was initially Margaret Dwyer. Secondly, she claimed to have come from a Protestant background when she was a Catholic. She lied about her age; on her marriage certificate she claimed to be 21, when she was actually 25. She was also lately known as a bigamist given her marriages with two men.

Despite of her diminishing popularity, The Passing of the Aborigines gives valuable descriptions of ceremonials, myths, and totems, and a discussion that remained debatable about cannibalism among the black people, including the eating of new-born babies. In the 2000's, the enormous information she gathered is used by indigenous groups seeking to establish their claims to traditional ownership of their land, and their rights to hunt, fish and look after sacred tribal sites in Southwestern Australia. Because at first Bates’ observation of the Aboriginal Native was not focusing on a specific tribe, during her long term involvement in the ethnographic research, she captured a vast amount of native tribes through her writing. She taught herself their language and mastered its diversity in which she claimed up to 155 dialects, and communicated effectively and later, contributed a lists of aboriginal vocabularies.

She travelled around the state by horse and camel buggy, and eventually focused her attention on the Nyoongar, the traditional landowners in the south-west. Then in 1912 she moved to South Australia, pitching a tent at Ooldea, on the edge of the remote and dry Nullarbor Plain, next to the route of the transcontinental railway, which was then in the process of being built. For the next 16 years Bates lived in that spot, with only a typewriter for company, surrounded by the complete works of Dickens and photographs of the British Royal Family.

During her settlement among the native, she published articles in several major newspaper in Adelaide, Brisbane, Melbourne, Sydney and Perth during 1901-1938. The excerpts of the articles were later compiled into The Passing of Aborigines. The originally intended book based on Bates’ extensive notes was never published until she passed away in 1951. Eventually the data was taken over and edited by Isobel White. The edited note was later published in 1985 under title The Native Tribes of Western Australia.

Given that the book was not intentionally made to be the final output of the lifelong study, it was indeed presented in a way how a fieldwork note written, particularly in a first person point of view. Borrowing the term from Clifford Geertz, the author placed herself not as a precise scientist but frankly as “human hand”. The writing was composed of narratives of detailed description and a variety of personal political view. Bates did neither refer to any literary works of other anthropologist as a supporting idea, nor she herself made an effort to synchronize the findings to any of established anthropological theories of the period.

Even if an ethnographic research is a highly personal experience, the autobiographical sense of this book is obvious and the scientific rigor is too vague. This ethnography was born in the time of transition of fieldwork tradition into a scholarly professional anthropology. For this reason, there is not yet a uniform theory but rather several theoretical perspectives of quite different character. Hence, it is difficult to measure the fit that existed between theory and method. Nevertheless, the amount of time spent for the expedition makes the weak integrated facts remained as a valuable information to be explored.

|

| Daisy Bates photographed with Jubaitch and his family who were camped at Maamba (Source: Brian Lomas) |

THE HEROINE OF THE MONOGRAPH

Inscribed in the introduction written by Alan Moorehead for the 1966 edition of The Passing of the Aborigine was list of things that Daisy Bates wasn’t. She wasn’t a missionary, as she did not try to convert or teach Australian Aborigines anything; she was not a doctor or nurse; she was not an anthropologist, although she ‘illuminated’ Australian Aborigines for non-Aboriginal Australians.

In the period where anthropology was a male-dominant field, Bates showed that the limitation could be turn into advantages. As Margaret Mead (1970) in her article Fieldwork in the Pacific believed that women has access to a wider ranger range of culture than does men, Bates succeed to obtain role flexibility during her fieldwork. Male ethnographers are usually restricted to the male world. While female ethnographers not only have access to the female world, the special knowledge possessed by women about genealogies, scandals, household budgets, but also considerable access to the male world too. (Barrett 209) The theory might be proved right.

Entering the intensive fieldwork by the age of 40, Bates demonstrated the centrality of kinship relationships among the Aborigines by showing how effectively she could deal with these persons once she was accepted as "Kabbarli" or spiritual grandmother. The tribal people of the Kimberley area, in far north-western Australia, held Bates in awe, believing her to be one of their reincarnated ancestors with superhuman spiritual and healing powers. With this position in which spread to other tribes through oral communication, she gained many exceptional access to dig out information about Aboriginal culture. She was even allowed to witness men's secret ceremonies and initiation rites, as a result of which she became an honorary initiated man.

How she earned the position might be as well a reciprocity of huge sacrifice she had done during the participatory observation. While she distributed her nearly sufficient allowance to buy clothes and foods and even cooked for them, the natives will come to her and share her their stories. While she offered a nurturing care for the weak among them, the natives embraced her as a family. At this point, given that she demonstrated a tireless endurance to reach a certain social position, it might be similar with the practice of prestige in the context of tribal people. Similar with the widely studied theory, Bates proved her inability to quit the mindset and apparently enjoyed the role she played.

Anthropology is frequently described in a way as the child of colonialism. The emergence and development of anthropology as a profession in Britain and Western Europe was linked to colonization of what eventually labeled the Third World. It is suggested that anthropologist help to soften the impact of colonialism by providing a more sensitive view toward the oppressed social organizations and contributing a voice towards a better treatment for the society. (Barrett 26)

In West Australia, after settler colonization, as Aborigines assessed their situation, they are divided into differed reactions. Some groups which waere called as The Wild Blackfellow, resisted and fought for their land and maintained that resistance. While others, called as station aborigines, adjusted to the prevailing white expansion by agreeing to work for the white man as a means of staying on their country. To overcome the situation, the government made a reciprocal arrangement by the handing out of rations as the trees and fruits of their land were replaced by livestock and planted crops. Daisy Bates stood in this setting and acted as real loyalist of the empire towards the natives. Every morning she dressed as how a respectable British woman would be, invited the natives for tea, and provided them a range of western fashions while at the same time had been called as ‘Kabbarli’.

As a noble Irish woman, once she proudly described her accomplishment to manage the first succeeded Aboriginal group performance in front of The Prince when he made his journey to the south. In another occasion, Bates told a story of a riot made by a group of natives demanding a new king from their own kind. With her shrewdness, she again succeed to compromise with them to accept the British Queen for she had provided them their needs and let them stay in their land. Bates certainly did not force them any religions but in a political perspective she spread an effective communicator of the imperial law in the Australian desert. Furthermore, she suggested an extreme patriarchal solution for the absence of governance within the Aborigines in a form of fatherhood of the Empire-makers, “men of the sterling British type that brought India and Africa into our Commonwealth of Nations-a Havelock, a Raffles, a Lugard, a Nicholson, a Lawrence of Arabia.” (Bates 281)

Geoffrey Gray in his book Cautious Silence (2007) believed that anthropologists in Australia in the period of 1920-1950, in spite of their concern about the fates of local colonized peoples, were invariably situated between contradictory forces. To enable access to the field, anthropologists were generally obliged to restrict criticism of the conditions and treatment of Indigenous people to within the funding body or sponsoring university, which was then expected to pass it on to the government department concerned with Indigenous affairs'. (Morton 3) In other words, anthropologists were rarely involved in anything that resembled activism. The book reaps some criticism of lacking samples of anthropologists which evidently deployed certain kind of activism at times. One of the aforementioned figure is Bates as described as “rather famously the stinging opposite of reticence when it came to pushing for reform of Aboriginal policy according to her own inimitable view” (Sutton 6)

At various times, the West Australian Government has tried experiments which were sincerely intended to improve certain conditions on Aboriginal health rate which at the period faced a serious problem of epidemic diseases. One of the experiment was an isolation hospital on Dorre and Bernier Islands, Shark Bay, which costed thousands of pounds. Bates through her newspaper articles showed how this experiment failed and how "the benefits devised by the white people and the endeavors to lighten their pain were only so much the greater aggravation of their exile.”(Bates 136) She also criticized Rottnest Island Native Prison in which captured huge amount of natives for breaking the Western law they never understand about and often with poor justifications. As she witnessed how tribal law worked, the treatment was considered misplaced as a kindness that killed as surely and as swiftly as cruelty would have done. Bates described how it was only another tragic mistake of the early colonists in dealing with the original inhabitants of a country so new and strange to them.

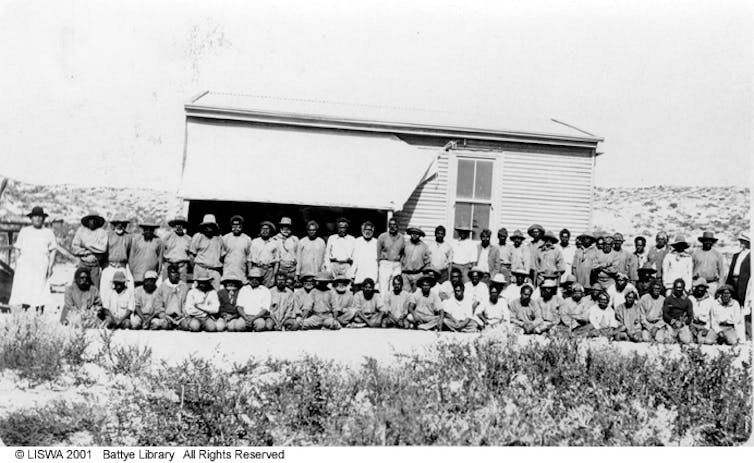

|

| Patients outside the hospital at Bernier Island. (Source: State Library of Western Australia) |

Several times in the text, Bates would elaborate her effort to think in natives’ mentality and in another part, as Aboriginal linguistic master, she would explain the complexity of translation during her observation. She herself stressed the importance of cultural relativism, even without mentioning the specific term, for the natives’ beliefs, values, and practices should be understood based on their own culture. However, as what has been discussed in the previous paragraph, her right leaning attitude was clearly expressed throughout the writing and in several other passages, she showed support toward evolutionism theory as well.

Before the rise of post modernism in anthropology, one’s ethnography was judged by the quality of the data and the elegance of the analysis. While with post modernism, it has been the author who taken the center of the stage. Reflections are done in a subjective attitude, i.e. how author knows the culture and interpret the data, how meaning is negotiated between the researcher and the researched, as well as self conscious musing on the subjective experience in the fieldwork. According to Clifford Geertz, what makes an anthropological text persuasive is not simply a matter of presenting a body of facts; it has much more to do with the author's ethos, with the power of his or her presentation. (Olson 2)

In the context of colonialism, anthropologists often start their involvement in the field with the same heroic spirit that the colonial regime descends. They were engaged in saving his or her own soul, by a curious and ambitious act of intellectual catharsis of the unfamiliar new world in their perspective, but also committed to recording and understanding his or her subject. Indeed, how some ethnography are written by positioning the anthropologists as hero arouses criticism regarding its scientific value in which becomes the endless debates of anthropology. In that situation, The Passing of Aborigines portrays Bates’ self creation, as a keen observer lingered in her contradictory morality throughout the expedition to ‘save the dying race’. To further extent, Bates takes the tools and perspectives of anthropology and uses them not only to produce elite theory for a narrow readership, but also uses the insights it generates into actions contributing to her obsession in easing the passing of Aborigines. This kind of activism raises questions about her ethnographic position, impact, possible over-identification with the subject she studied, as well as distinctions between theory and action.

REFFERENCES

C. H. “The Geographical Journal.”The Geographical Journal, vol. 93, no. 3, 1939, pp. 268–269. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1788386.

Barrett, Stanley R. “Anthropology: A Student’s Guide to Theory and Method.” University of Toronto Press. 1996

Bates, Daisy. “The Passing of Aborigines.” University of Adelaide Press. 1938

Burridge, K. O. L. “The Geographical Journal.” The Geographical Journal, vol. 132, no. 4, 1966, pp. 549–550. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1792576.

Colley, Brockwell, Gara and Scott Cane. “The Archaeology of Daisy Bates' Campsite at Ooldea, South Australia”. Australian Archaeology No. 28 (Jun., 1989), pp. 79-91. Taylor & Francis Ltd. www.jstor.org/stable/40286903

Hartman, Tod. “Beyond Sontag as a reader of Lévi-Strauss: ‘anthropologist as hero’”. Anthropology Matters Journal 2007, Vol 9 (1)

Moorehead, Alan. “Foreword to Daisy Bates, The Passing of the Aborigines: A Lifetime Spent Among the Natives of Australia”. Melbourne: Heinemann, 1966, ix

Morton, John. “The Journal of Pacific History.” The Journal of Pacific History, vol. 44, no. 1, 2009, pp. 117–118. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40346707.

Olson, Gary A. “The Social Scientist as Author: Clifford Geertz on Ethnography and Social Construction.” Journal of Advanced Composition, vol. 11, no. 2, 1991, pp. 245–268. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/20865794.

Sutton, Peter, and David McKnight. “Australian Anthropologists and Political Action 1925-1960.” Oceania, vol. 79, no. 2, 2009, pp. 202–217. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40495613.

Wood, William W. “Social Science Quarterly.” Social Science Quarterly, vol. 49, no. 2, 1968, pp. 384–385. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/42858379

0 comments